The purpose of the Unicorn Tapestries must have been very important, considered the staggering amount of time and resources put into them – comparable to buying a luxury home today. Their mission went beyond mere aesthetics: they told a story, or better, a story inside a story, lending the same scene to many levels of interpretation. To read their true narrative is to decipher the myriad of clues hidden inside the artworks, which is exactly what we will investigate in this article.

At the end of the article, we will also try to answer the age-old question whether unicorns are real or not - and find out why medieval people were sure about their existence.

ORIGINS

Possibly woven to celebrate a royal marriage, that of Anne of Brittany and King Louis XII of France, the Unicorn Tapestries were likely commissioned in the Netherlands, which at that time was the mecca for luxury tapestry production.

We are in the late Middle Ages (somewhere between 1495 and 1505), and producing a tapestry required the involvement of many different trades. The patron would not directly commission the artist like we do today, but he would pay an entrepreneur (called “merchant-producer”) who took care of sourcing the materials, setting up the shop, and finding the artists and weavers needed to complete the job. Written contracts were binding all these parties, very much like today.

For the Unicorn Tapestries, the merchant had to order the highest quality silks, wools, and precious metal yarns; the threads were dyed inside the shop, to get exactly the right hues. Then an artist was commissioned to paint a so called “cartoon,” a painting that would serve as the pattern for the weavers to follow – this painting was in fact placed right under the loom. Many merchants reused the cartoon to reproduce the same tapestries over and over, but this was out of the question for the Unicorn Tapestries: the set had to be exclusive, and the cartoon was surely returned to the patron as soon as the work was finished.

The tapestries were destined to hang on the walls of the castle where they served many purposes: insulation against the cold, and status symbols for the powerful elite. Only the extremely wealthy could afford a tapestry - the less wealthy settled for paintings imitating tapestries.

A NEAR-FATAL JOURNEY

At a certain point, the Unicorn Tapestries were moved to the French town of Verteuil, where the noble family La Rochefoucauld owned their family chateau. Nobody at the time could imagine the future course of events.

Centuries passed for the undisturbed tapestries, but then the French Revolution exploded and all artworks containing symbols of aristocracy were destroyed. The Unicorn Tapestries too contained the royal arms of France and when the populist mob looted the chateau in 1793, these works were bound to be burned.

[Many aristocratic ciphers were present throughout the tapestries]

This was the beginning of the Reign of Terror (1793-94), that period of anarchy following the revolution, during which even the vocabulary of people was scrutinized; any mention of the traditional aristocratic titles was enough to be labeled as traitor and hung.

The tapestries ended up in the hands of a local committee and there is no doubt that it was their beauty to ultimately save them. The royal arms of Anne and Louis’ families, once present in all sky areas, were cut away to eliminate the most visible signs of aristocracy. We don’t know who did it and at what point this trimming took place, but we do know from the records that the overseeing committee instructed, “Respect them because they show no signs of royalty; they contain stories.”

This is where we lose track of the Unicorn Tapestries, for over half a century.

They would be recovered in the early 1850s in a barn where they were used to cover vegetables. The farmer believed they were “old curtains.” The tapestries, now in poor conditions, were bought again by the heirs of the La Rochefoucauld family where they stayed until 1922, when John Rockefeller Jr. bought them for his specially designed room in his New York residence. Finally, in 1937 the tapestries were acquired by the MET where they are still one of the most popular attractions.

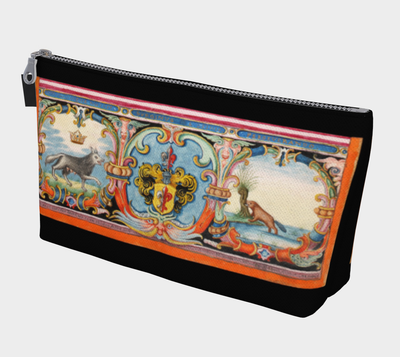

At MedievalMade we engaged in a detailed digital restoration before reproducing the tapestries onto our products. We reconstructed all missing areas and the discordant patches that were added as repairs over the centuries; the colors were also brought back to the vibrancy they must have had originally. Our conservative restoration preserved nonetheless the characteristic signs of organic aging, showing the authenticity of these medieval artworks.

[Before and After restoration by MedievalMade]

ONE UNICORN, MANY MEANINGS

The Unicorn Tapestries have both religious and secular meanings. The same unicorn can represent Christ, a newlywed husband, and a lover – all at the same time. This can appear strange to a modern audience, but it was very normal during the Middle Ages. It was common to combine several allegories into one thought or image simultaneously.

“The Unicorn Purifies Water” is one of the most beautiful scenes of the whole tapestry set and certainly one of the most significant for all the allegories that it combines.

The Unicorn as a symbol of Christ

Here the Unicorn is seen kneeling in front of a water stream that is purifying with his horn, so that all the other animals can drink. It is a sacred moment, as all the wild creatures sit, subdued, in perfect harmony. On the background, however, danger lurks. A man is pointing at the unicorn, drawing the attention of the hunting party and their many hounds. The unicorn could easily escape, or even kill the hunters given his enormous strength and speed that surpasses all existing animals on earth. But, on the contrary, he lets the men approach him and eventually, on the following scenes, kill him. Why?

The reason is that here the unicorn is a symbol of the Passion: the Unicorn-as-Christ always allows his hunters to capture him because He willingly embraces his sacrifice.

We at MedievalMade advanced the possibility that, perhaps, the 12 hunters might also represent the 12 apostles, as being instrumental to the greater plan of Christ’s sacrifice. We also noticed a similarity in composition between this scene and the Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci: the subjects are both perfectly split into six to the left and six to the right; also the subgroups that they form, in clusters of three, seem to echo each other. The Last Supper was completed between 1495 and 1498, exactly in the same timeframe as the unicorn tapestry (dated between 1495-1505). We wonder if they were influenced by the same composition styles common at the time, and how. It might be a simple coincidence, but so many unanswered questions remain about the Unicorn Tapestries that everyone is invited to advance hypothesis unexplored so far.

[The Last Supper vs. The Unicorn Purifies Water]

The hunt of the unicorn as a Love Story

Let’s remember that these tapestries were likely commissioned for a wedding, so their patrons took great pleasure into seeing their personal story celebrated as well into the artworks. It was not a stretch of their imagination, as the allegory of the Unicorn-as-Lover had been widely represented throughout the Middle Ages in many works of art.

In this allegory, the unicorn represents the Lover and the Maiden is his Beloved. The hunter is the personification of Love itself, a helper so to speak, that helps the maiden subdue her lover and brings him into the marriage. This interpretation of the Unicorn-as-Lover is perfectly reflected in this scene of the set, the Unicorn in Captivity (aka, Unicorn in the Garden).

Here the Unicorn rests inside an enclosed garden, wounded and bleeding, but showing no expression of pain whatsoever. Like Cupid and his darts, everyone knew that the hunter was Love itself and could not inflict physical harm.

This is why we chose to conceal the wounds during our digital restoration, and offer a more straightforward reading of this artwork to our modern audience. The wounds inflicted on the unicorn made perfect sense to the medieval people, but today they would not be interpreted as the happy ending they were meant to convey.

[In the MedievalMade restoration, the wounds are eliminated and the colors revived]

Here the Unicorn-Lover lives happily in an enclosed garden, symbol of his commitment in marriage. He is chained to a pomegranate tree, the symbol of fertility; the pomegranates hint to the consummation of marriage.

A symbol for the Incarnation

The unicorn chained to a tree within a fenced garden also represents the Incarnation: Christ, the spiritual unicorn, entered the Virgin womb for the salvation of humanity. The fenced area is the Virgin’s enclosed garden, the Hortus conclusus.

This allegory has very ancient origins and can be traced down to a book called Physiologus, probably written around 200 A.D. in Alexandria. The book described a way to capture the powerful unicorn that no man or beast could ever catch. Only a virgin could tame him. Attracted by her purity, the creature would place his head on her lap, and fall asleep.

This description of a virgin taming the unicorn inspired the association with the Virgin Mary. The capture of the unicorn by the Virgin Mary is referred to as the Mystic Hunt, and became a popular subject in Christian art during the Middle Ages. Also the Unicorn Tapestries included this scene, but unfortunately only two fragments remain today. They are nonetheless full of clues.

[The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden]

The hunter blowing the horn likely represents Gabriel, and his hounds are the so called Four Daughters of God: Veritas (Truth), Justitia (Justice), Pax (Peace), and Misericordia (Mercy); they argue for or against Man, as the Trinity ponders whether to punish or forgive humankind for their sins. It is here that Christ, the Unicorn, offers to become incarnate, therefore redeeming humanity.

He enters the wooden fence, a symbol for the hortus conclusus, and he smiles while being attacked. He smiles at the woman in front of him (only her hand remains visible, caressing his neck): this woman is surely the Virgin Mary. Another woman with a treacherous look, the one fully visible on the fragment, stands behind the unicorn: she must be Eve. The apple tree inside the garden is likely to be the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which in fact grew in the Garden of Eden.

The Unicorn as symbol of Everyman

Finally, the unicorn is also the symbol of Everyman, who faces trials and obstacles when proceeding from birth to death. The hunters who chase him are the characters of Vanity, Ignorance, Old Age, and Illness. The hounds represent all the human emotions that hinder his progress through life, for example Anxiety, Fear, Impulsiveness, Desire, etc.

We can all relate to this unicorn and his journey through life. His struggles are as relevant today as they were in medieval times, showing as the human condition has always experienced the same emotions and questions having to do with the meaning of life itself.

ARE UNICORNS REAL?

It could make us smile and label medieval people as credulous for believing in unicorns. But after analyzing historical clues, we must rethink our position. Perhaps, they had some good reasons to believe in unicorns.

The first description of a unicorn comes from a Greek doctor named Ctesias who lived in the 4th century BC. Ctesias reported in his book what many travelers visiting India had told him:

“A wild donkey, the size of a horse and with a single horn on its forehead,” he wrote. "The whole of their body is white, except their head, which is close to purple, and their eyes, which glow with a dark blue color." He went on reporting that the horn was at least a cubit and a half long. 1 Biblical Cubit was the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger, estimated at 18 inches (about 45 centimeters), which means the unicorn horn was reported to be at least 27 inches or 2.25 ft (about 68 cm).

Similar accounts followed along the centuries and an important detail was added by a Roman naturalist, Aelian (A.D. 170-235), who stated the horn had a spiral pattern. Might perhaps be that the tusk of a narwhal was already known during the Roman empire and mistaken for a unicorn horn?

Let’s however notice that the narwhal’s tusk is white, whereas all accounts described the unicorn’s horn as black. Could this be a sign that the unicorn truly existed before becoming extinct, and had nothing to do with the narwhal?

Assimilating the unicorn to any existent species never worked. For Ctesias, the unicorn belonged to the family of donkeys; Megasthenes, a Macedonian ambassador in Persia in the 3rd century BC, described it as a horse with a deer's head; Aristotle associated it to the Indian donkey and the oryx of the Namibian desert, both single-horned animals. This points to the fact that the unicorn was neither a donkey nor a stag or a horse, but rather its own species, likely related to other similar species - the same way a mule is related to a donkey.

However, all historical accounts agreed on one trait: they stated that this creature was incredibly fast and strong - several sources described how the unicorn prevailed in combat against wild elephants, using its horn against the elephant's belly. This is how stories started to emerge about the miraculous powers of the unicorn's horn. It’s not uncommon in human history to take the true qualities of a creature (ex. the power of a shark) and associate magical qualities to one of its body parts (ex. the tooth of a shark believed in many cultures to give strength and masculinity to the wearer). This is where possible fact, an existent but extinct species, mixes with fictional accounts.

The Unicorn Therapy

During the Middle Ages a trade of narwhals’ tusks became prominent all over Europe, being sold as unicorns’ horns. For example Queen Elizabeth I received one in 1577 by a famous captain who claimed to have encountered a “Sea unicorn.”

The tusks were used to build eating and drinking utensils. Even the fragments were sold to test suspicious liquids, or to be ingested as medicine to build up immunity against poisons and illnesses.

The “Unicorn Therapy” was administer by apothecaries and physicians well until the 18th century!

CONCLUSIONS:

We will never know for sure whether the unicorn was a true but extinct species or a totally fictional creature - at least, not until more studies are done and fossils uncovered.

But what we know is that this creature, like no other, has inspired a whole universe of artworks with very special meanings. When looking at the unicorn, we are immediately taken to a positive emotional place, and perhaps this is the true power of the unicorn, the power it holds in our minds and hearts.