There is a set of illustrations that has fascinated people since the 1500’s and that go beyond grotesque, even for the standards of that period. We brought to life some of these illustrations and we confirm what many have said before, that they seem to have been conceived by a crazy (or drunk) person. However, it’s in this very madness that some wise lessons are given.

Lesson 1: Don’t go to war when you’re drunk.

Can we always trust our leaders to make the best decisions? People asked this same question in the past, and the answer was not always flattering.

[A parody of a leader holding a flag, a sword…and a bottle of wine]

Lesson 2: You need insanity to see the truth.

As Aristotle said, “There is no great genius without some touch of madness”.

In the case of French writer François Rabelais, the appellatives of crazy and genius totally overlapped. He started out as a physician, scholar, diplomat, and Catholic priest, but later became a controversial satirist. His Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel depict larger-than-life characters which are extravagant caricatures of Medieval and Renaissance society.

[“Potato Sac Scarecrow” is how we named this strange character in medieval rags]

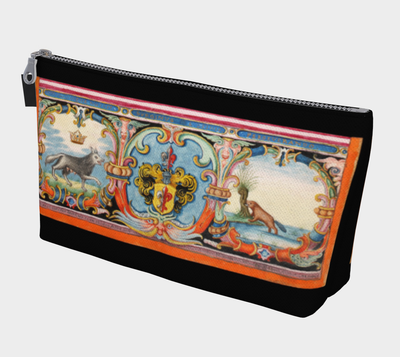

Lesson 3: Don’t trust a walking pot just because it promises to cook for free.

Is anything really free? This was another great question of the past (that still resonates today). Gargantua first, and his son later, soon realize that negotiation is the most common currency in all the places they visit. And when things are apparently free, they often hide a higher hidden price or agenda.

[A walking pot, a wine bucket… or perhaps a potato inspired this character]

Apparently absurd, the work of Rabelais uses laughter to treat the great questions of his time like education, religion, and politics.

For example, he derides medieval scholarship when he writes that Gargantua impresses his father with his intelligence and is entrusted to an important tutor; but his education renders him a great fool, and he is later in need of reeducation.

Caught up in the religious and political turmoil of the Reformation, Rabelais mocks many aspects of the Catholic religion like ritual prayer, the traffic in indulgences, monasticism, but also criticizes its converse, dogmatic Protestantism.

Lesson 4: What goes around comes around.

Rabelais conceives the idea of karma beyond the religious dogmas of his time. He is sure: karma is here, now, and it doesn’t need to wait for the afterlife. The monk who loves eating doesn’t even stop when he is captured and admonished by the frog - because the monk loves his sin. Will he be spared or will he die of his same sin? Watch out, Rabelais says, because the prey can always become the predator.

[In a bizarre twist of roles, the greedy monk is captured by the alchemist frog]

Lesson 5: Don’t easily trust people, just because they are well dressed.

No one should be above scrutiny, no matter how powerful they are. For example Rabelais lampoons emperor Charles V, implying that his policies are tyrannical.

His work plays with words and double senses, to the point that it is stigmatized as obscene by the censors of the Collège de la Sorbonne, and his contemporaries avoid mentioning it. It features “erudition, vulgarity, and wordplay”, they comment at that time.

[Sexual satire was easily understood by common folks as a warning to not easily trust clergy and politicians just because of their position]

Rabelais has frequently been named as “the world's greatest comic genius" and his work has regularly been compared with the works of William Shakespeare.

Parodying everyone from classic authors to his own contemporaries, the dazzling and exuberant stories of Rabelais expose human follies with mischievous and often obscene humor.

His genre has been defined as grotesque realism.

Both ecclesiastical and anticlerical, Christian and a freethinker, a doctor and a bon vivant, Rabelais is contradictory and never apologizes for it. His purpose is not to provide answers, but only a framework for critical thinking.

He raises the questions, then everyone can look for their own answers.